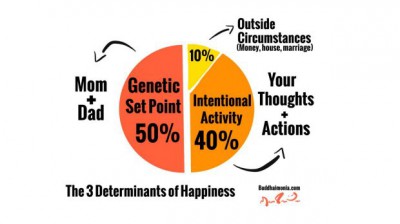

The “happiness pie”, genetic and environmental determinism, and free will

Nick Brown and Julia Rohrer recently posted a new preprint titled Re-slicing the ”Happiness Pie: A Re-examination of the Determinants of Well-being that comments on an influential paper by Lyubomirsky, Sheldon, and Schkade (2005) on the determinants of well-being. Nick Brown is the amateur who debunked the mathematics of happiness (together with the legendary Alain Sokal of the “Sokal hoax”). He has made a name for himself exposing shoddy work in positive psychology. This is another addition to this genre. What is particularly mind-blowing with this one is not just the sheer lack of intellectual sophistication of the criticized paper, but the fact that it has produced a whopping 3000 Google Scholar citations.

The central claim of the Lyubomirsky et al. paper is that roughly 50% of the variance in well-being can be explained in terms of genetic predispositions and that roughly 10% of it can be explained in terms of life circumstances, leaving up to 40% to be explained in terms of intentional activity. This decomposition of the determinants of well-being, which has come to be known as the happiness pie, has become a cornerstone of the self-help and coaching movements, as it appears to suggest that all persons have considerable control over their own well-being.

Problems pointed out by Brown and Rohrer

Brown and Rohrer meticulously pick the happiness pie apart. Here are some of the errors:

1. An additive model that divides the determinants of well-being into three disparate portions (or pieces of a pie) is only meaningful if all the portions are independent of each other. But there is plenty of evidence of interactions between genes, environment, and volitional activity.

2. No evidence is presented that the “leftover” variance after taking genetics and the environment into consideration can be attributed to volitional activity.

3. Measurement error, which attenuates estimates, has not been taken into consideration. If we adjust for this, there will be less “leftover” variance.

4. When the sources for the numbers 50% and 10% are re-examined, these numbers appear to be arbitrary, and how they were derived is not transparent.

5. Particularly the 10% estimate appears based on sloppy reasoning. Countless environmental factors are not measured in the survey studies that this estimate is based on (in utero influence is a dramatic example). Environmental factors are frequently operationalized in terms of demographic variables (which have both genetic and environmental determinants and do certainly not exhaust the full range of relevant life

circumstances).

6. Even if the 50% and 10% figures and the subtraction logic by which 40% of the variance is leftover for intentional activity were correct, this would still just be a population average. It would not imply that each individual has substantial control over his or her well-being.

Moving beyond the Brown and Rohrer paper

The great irony of all this is that there is nothing here—neither in the Lyubomirsky et al. paper nor in the Brown and Rohrer paper—showing that people cannot change their well-being through intentional activity either. The deeper problem is that claims about the effects of will-power (and to an even greater degree claims about free will) do not have anything at all to do with heritability and environmental influences per se. The proper way to scientifically investigate the extent to which people can intentionally change their well-being is to:

(a) recruit a large group of persons who are highly motivated to do what it takes to increase their well-being,

(b) make sure that they have all relevant resources (or at least measure whether they do), including the best forms of therapy or training programs, time, money, etc., and make sure that they actually do what they are supposed to do,

(c) measure changes in their levels of well-being compared to a control group of persons who do not engage in deliberate efforts to change their well-being but who are otherwise comparable to the group of persons who do.

Obviously, this is not easy to do (e.g., how do we make sure that experiment and control group are comparable?), and even if done well, all that we could say is that this is what we can achieve with our current state of knowledge. It is possible that there are effective methods for increasing well-being that have not yet been discovered or are not widely known.

Heritability coefficients and estimates of environmental correlates in a general population are in themselves irrelevant to this question because we do not know whether the persons who participated in these studies did engage in persistent intentional efforts to change their well-being or whether they had access to the best strategies for doing this. These pieces of information could possibly have some relevance if we would know which individuals had the motivation and strategies necessary for deliberate improvement of well-being and which did not. Even so, intentional orientations do not emerge randomly out of thin air—they may be related to traits such as consciousness or openness to change, which have a sizable genetic component—so it might be tricky to find twins who differ enough in this regard.

At any rate, a case can be made that people do at least have the capacity for intentionally changing their well-being if they are motivated to make enough changes to their lives, without resorting to any of the dubious arguments presented by Lyubomirsky.