Five myths about the Big Five personality model

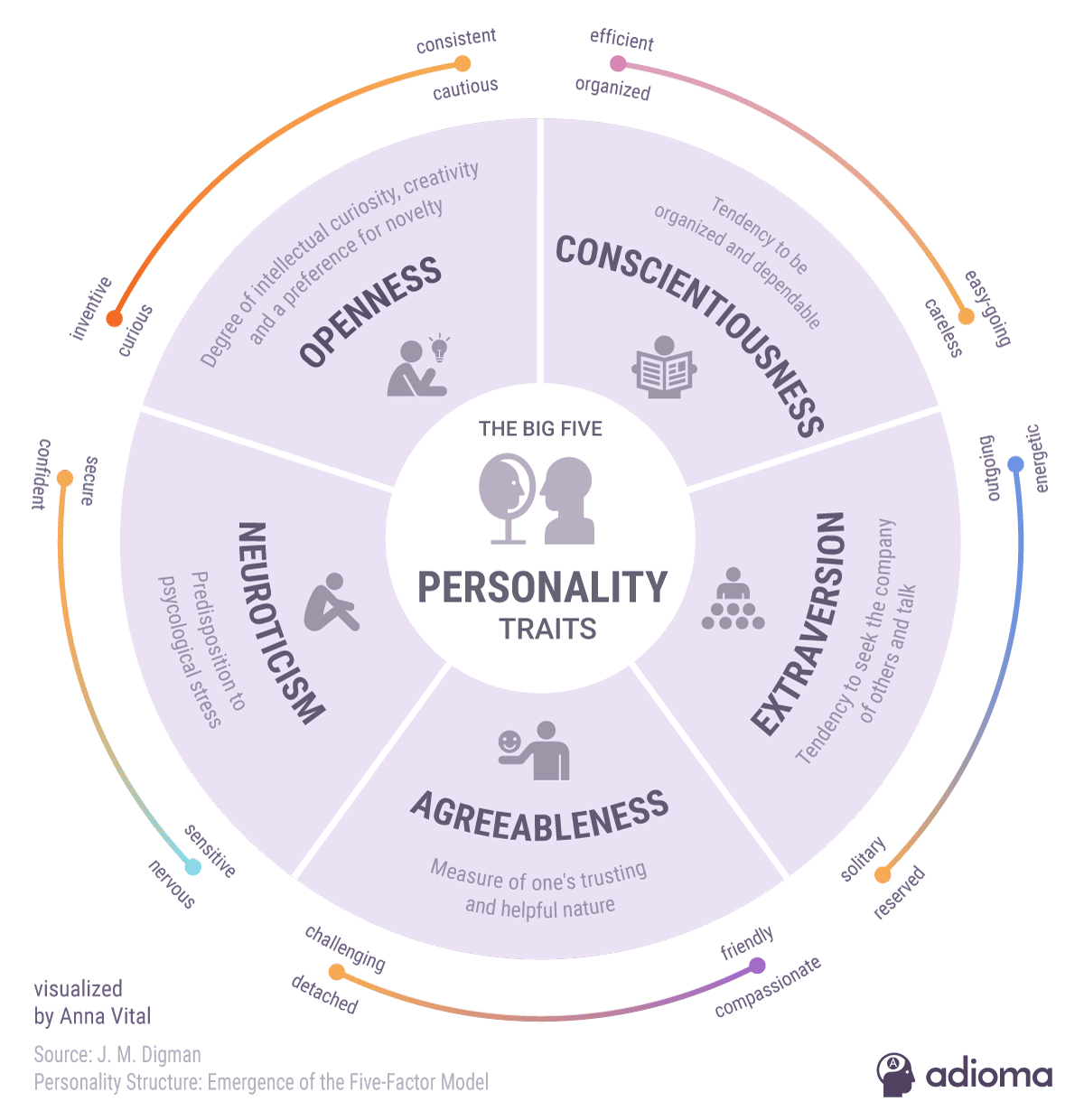

Most people who are interested in psychology have probably heard of the Big Five model, which divides personality into five traits: extraversion, neuroticism, conscientiousness, agreeableness, and openness. It is often depicted as The model of personality—the holy grail of personality psychology.

Sometimes a dichotomous contrast is made between pseudo-scientific models, such as the Myers-Briggs, DISC, or enneagram models, and the scientific model of personality—that is, the Big Five. The pseudo-scientific models are flawed for two main reasons: (1) they capitalize on and bolster categorical and simplistic thinking about personality in everyday life, as well as people’s need for a positive self-image, and (2) they are not supported by scientific evidence. The Big Five model is vastly superior. It is dimensional rather than categorical (i.e., each individual has a score along each continous dimension), it is supported by scientific evidence, and it is useful for capturing variation between individuals and predicting behavior in many contexts.

There are, however, several persistent myths concerning the status of the Big Five model. The ubiquity of these myths among psychologists, behavioral scientists, and practitioners is embarrasing.

1. There is a scientific consensus that personality is equivalent to the Big Five

There may have been something like a broad consensus on the equivalence of personality and the Big Five at some point in the field’s history, between 1990 and 2010. But particuarly over the last decade, personality psychologists have moved away from the single-minded obsesssion with the Big Five model. Although most personality psychologists probably still feel that the Big Five is one useful personality model that identifies some important personality characteristics, the notion that personality is reducible to the Big Five is on the decline (rightly so).

2. The Big Five are cut into the joints of nature

There Big Five are sometimes described as cut into the joints of nature in a manner similar to the basic elements of chemistry. To understand why this is inaccurate, consider how the Big Five model was constructed in the first place: It was generated from statistical analyses of responses to gigantic sets of personality descriptors. The statistical method in question is factor analysis with varimax rotation. What is important to note here is that the “varimax rotation” part is included to minimize correlations between the factors that are identified (or rather generated) from the analyses. It is imposes a simplified structure on the data, usually to facilitate interpretation. We know today that when a so called oblique rotation is used, to allow the factors to correlate and thereby represent the data in a more straightfoward (or true) way, the factor model that is generated becomes a lot more complex and messy. What is more, when confirmatory methods are used to fit the simplified model, with five independent factors, the model fit is often poor. In other words: by its very nature, the Big Five model is a simplification, albeit a useful one. The truth is more complicated.

3. There are exactly five basic personality traits

A related myth is that there are exactly five factors. This is inacurrate because the optimal number of factors to include in the model depends on the what purpose the model is used for. If the goal is to capture maximal variation in personality and achieve maximal predictive power then considerably more factors than five (probably dozens) are needed. If the goal is instead to make meaningful generalizations and comparisons across cultural contexts, then the optimal number of factors is lower than five (probably between one and three). In other words, there is no single all-purpose personality trait model that performs best in all contexts. The Big Five is a practically useful model, probably in part because a five-factor solution constitutes a pragmatic tradeoff between predictive power and generalizability—and it has been practically advantageous historically to unite the research community and practitioners around a single paradigm.

4. The Big Five capture human individuality

A fourth myth is that an individual’s personality is just his or her levels of the Big Five (or similar) traits. As mentioned above, the Big Five model is based on factor analyses of personality data. Factor analysis is a method for identifying differences between individuals rather than structures within individuals. When a factor such as extraversion emerges from the analysis, this means that people differ a lot in terms of extraversion. It does not mean that extraversion exists within each individual, let alone that it is an internal causal structure that emits behavior akin to a biological organ. Factors are mathematical idealizations that are generated to capture abstract patterns in populations. At best, they represent something like “the average person” rather than each individual person. Furthermore, traditional personality trait models like the Big Five model fail to capture the individual’s beliefs, values, goals, life stories, and worldviews in general—and these personality characteristics are particularly important to take into consideration when we are trying to understand an individual person of flesh and blood. The Big Five is akin to a “psychology of a stranger”—it helps us to form a rough first impression (or draft) of the contours of personality when we encounter a stranger, but to really know what a person is like deep down, we need to fill the portrait of personality with life. We need to understand the personal worldviews that infuse behavior and experience with meaning and direction, as well as unique constellations of dispositional traits and variations across contexts and time points within the individual. Relying exclusively on Big Five scores when trying to understand an individual is simplistic, shallow, and misguided.

5. The Big Five are more basic than other personality characteristics

A classical idea in personality psychology that is crystallized in the so called five-factor theory is that the Big Five traits are in some sense more basic than other characteristics. They have, for instance, been portrayed as inherently universal, decontextualized, and biology-based temperamental characteristics, while beliefs, values, goals, life narratives, and other characteristics have been portrayed as culture-dependent, contextualized within time, place, and social roles, and rooted in socialization and life experiences. The Big Five have also been portrayed as the core of personality, in the sense that all the variation in other personal characteristics that is due to personality rather than culture and environmental influences is assumed to be reducible to the Big Five (e.g., people are assumed to have different goals solely because they are extraverted, neurotic, open, and so on, and because they are have been exposed to certain environments). These assumptions are neither grounded in clear theoretical analysis nor supported by empirical evidence. There are, for instance, types of beliefs and values that recur with the same degree of universality across cultures and exhibit similar cross-temporal stability and heritability as the Big Five traits, and the traits can become impregnated by culture and changed by life events, at least to some extent; and there are complex and mutual causal effects as well as covariation that is due to common genetic underpinnings between different personality characteristics of different types.

Some readings

De Raad, B., Barelds, D. P. H., Levert, E., Ostendorf, F., Mlačić, B., Blas, L. D., Hřebíčková, M., Szirmák, Z., Szarota, P., Perugini, M., Church, A. T., & Katigbak, M. S. (2010). Only three factors of personality description are fully replicable across languages: A comparison of 14 trait taxonomies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(1), 160–173. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017184

Kandler, C., Zimmermann, J., & McAdams, D. P. (2014). Core and surface characteristics for the description and theory of personality differences and development. European Journal of Personality, 28(3), 231–243. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.1952

Lamiell, J. T. (2000). A periodic table of personality elements? The “Big Five” and trait “psychology” in critical perspective. Journal of Theoretical and Philosophical Psychology, 20(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0091211

McAdams, D. P. (1992). The five-factor model in personality: A critical appraisal. Journal of Personality, 60(2), 329–361. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1992.tb00976.x

Nilsson, A. (2014). Personality psychology as the integrative study of traits and worldviews. New Ideas in Psychology, 32, 18–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.newideapsych.2013.04.008

Saucier, G., & Iurino, K. (2020). High-dimensionality personality structure in the natural language: Further analyses of classic sets of English-language trait-adjectives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 119(5), 1188–1219. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000273